Life of Breath PhD student Tina Williams shares her blog post from the Life of Breath Blog (original post) on her experiences exhibiting at this year’s Research without Borders festival of postgraduate research.

The 2017 Research Without Borders Festival showcase exhibition ran at Bristol’s Colston Hall on May 12th. I, along with ninety-nine other research students, took part in this engaging research exhibition, with the aim of answering the call to address pressing ‘twenty-first century challenges’ by creating ‘a common language & framework that can transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries’ (Bristol Doctoral College, Research Without Borders Programme, 2017).

Presenting philosophical concepts, ideas, and theories relevant to challenges such as the rise of respiratory conditions and anxiety disorders in a tactile and interactive manner was certainly a challenge, because philosophy is usually discussed within academic conferences, the classroom, journal articles and so on. Conveying the utility of philosophical ideas to contemporary living outside papers, posters or soundbites without losing the impact and message of, for example, phenomenological insights into human existence was always going to be difficult.

My exhibit was included in the ‘Perspectives for Looking at the World’ section. Here, alongside other PhD researchers working in areas including neuro-psychology and neuro-imaging in Alzheimer’s, Middle English debates on the body and soul, colour in Lorca’s theatre, I presented my exhibit ‘Suffering in Silence’. The purpose of the exhibit was to raise the profile of the invisible yet highly prevalent rates of breathless experiences in modern human experience, shine a light on the excellent work of the Life of Breath Project and its members, and to incorporate the utility of exploring phenomenological accounts of changes to embodiment, relationships, and society by respiratory and mental health conditions. This of course includes looking at the experiences of the embodied person and how their condition transforms their way of being-in-the-world, relations with others and their environment as they struggle to catch their breath on, for example, the walk upstairs or to the local surgery, and the relationship with clinicians and the scientific understanding of the impact of illness on the whole person, instead of the medical focus on disease processes. In short, we need to focus on the phenomenology of these experiences:

For many years, our knowledge of children and the sick was held back, kept at a rudimentary stage, by the same assumptions: the questions which the doctor or researcher asked of them were the questions of an adult or a healthy person. Little attempt was made to understand the way that they themselves lived; instead, the emphasis fell on truing to measure how far their efforts fell short of what the average adult or healthy person was capable of accomplishing. (Merleau-Ponty, World of Perception, p. 55).

The doctoral college provided intensive training to hammer home the message of thinking outside the usual poster presentations; interactive displays and tactile artefacts were just two suggestions. With these in mind, I set upon creating an exhibition that could be an embodied experience as well as represent and evoke anxiety, restricted embodiment, and entrapment often experienced in respiratory conditions or anxiety disorders. This led to the construction of the Restricto-Box: a narrow telephone box-shaped prop that could induce anxiety, the closing-in experience of claustrophobia, and the restriction of both the body and the environment when one is trapped in the moment of breathlessness. These are experiences that those with chronic illnesses, certain disabilities, or panic anxiety often report. My exhibit intended to give voice to these invisible, suffocating, and socially isolating experiences, as, explained during the 3MT (3-Minute Thesis) semi-finals (which I also took part in), ‘when the breath is stifled, the voice is silenced, communication cut off’.

Existentially, breathlessness is a constant reminder of impending mortality. Most of us want to die in our sleep with no knowledge of the event. Not only do patients with chronic, progressive lung disease know of their impending death months, years or decades ahead of the day [6], they fear how they will die, with the fear of suffocation always somewhere in their minds. This is as frightening as life can be.

(Currow and Johnson, 2015)

This part of the exhibition in particular was received ‘well’: “It is horrible!”, “Get me out!”, and many other expressions of the unpleasant experience of being inside were reported on the feedback cards. Attempting to make the most out of the space, I included within the box examples of changes to embodiment as described by patients and philosophers, particularly in the work of phenomenologists Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Havi Carel.

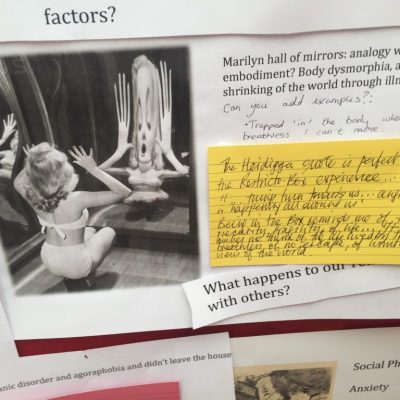

Indeed, a Heidegger quote I presented was included in one of the comment cards (also visible in the image above):

The Heidegger quote is perfect for the Restricto-Box experience… ‘Things turn towards us… angst is happening all around us’. Being in the box reminds me of the precarity, fragility of life… it makes me think of the life lived by the breathless of no escape, of limited views of the world.

I also included images of distorted embodiment; famous sufferers such as Charles Darwin, who was agoraphobic and suffered from terrible panic attacks that left him breathless and housebound; reports on the shockingly poor air quality of UK cities, workplaces and homes; NASA recommendations for indoor plants to naturally get rid of toxic particulates such as formaldehyde; and journal accounts of related disorders and their impact on patients’ whole worlds, in the hope of informing, contextualising and de-stigmatising these disorders. Staff and students from areas as diverse as professionals in the doctoral college to research laboratory work in formaldehyde-rich environments engaged with my display and discussions, commenting on their own experiences of poor air quality, asthma and panic experiences, social deprivation in their home towns, and concerns about the impact of the polluted environment on their health.

Finally, I incorporated a model of the lungs. One side was damaged by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Squeezing the attached bellows to inflate or deflate the lungs demonstrated hyperinflation of the lungs, visibly protruding, black, and inefficient in comparison to the healthy lung. Additionally, philosophical texts, posters, and information on the Wellcome Trust-funded Life of Breath project and staff was included, so that I could show the important work that members from Bristol and Durham are doing. I was extremely honoured to have my exhibit highly commended, and thank both the team and the Doctoral College for their hard work and all the support given to me.