Did you know that the world’s longest-living animal was a clam that lived to be 507 years old? “Ming” (named after the dynasty it was born in, of course) was found off the coast of Iceland in 2006, and spawned a surge of research into the extreme lifespans found in nature. Ranging from just minutes in the adult mayfly, to animals like Ming that can live for several centuries, the diversity of lifespans across the animal kingdom is astounding. And what’s even more fascinating is that rates of ageing also differ hugely across different species. With “ageing” defined as the increasing risk of mortality over time, some animals seem to age much more slowly than others – and some don’t actually seem to age at all.

My PhD work focuses on lifespan and ageing in Heliconius, a group of neotropical butterflies that can live for a prodigious six months (pretty impressive for a butterfly!). What I find most interesting about this research is its dissection of these differences in ageing across different species. All animals are made up of the same molecular building blocks, and yet some have managed to extend their lifespans and even escape ageing altogether – teaching us that lifespan is not necessarily immutable, and ageing may not be inevitable.

I’ve always been interested in public engagement (and have been known to go to a few music festivals in my time), so when I saw a call for applications for science stalls for the Welsh music festival Green Man, I knew I wanted to apply – and that I wanted to teach people about this amazing diversity in animal ageing. But I needed a hook. How could I convey these ideas in an accessible, interactive way, that would work in a setting like a music festival?

One of my favourite pieces of ambient music is a series called The Disintegration Loops, by the composer William Basinski. Interested in the deterioration of analogue media over time, Basinski created a series of loops using magnetic tape, the kind you find in old cassettes. As you listen, you can hear the audio loops gradually decay as the physical tape disintegrates. I thought we could use a similar kind of audio processing to represent the diversity in ageing displayed by different animals, with a programmed decay that matched that animal’s ageing curve.

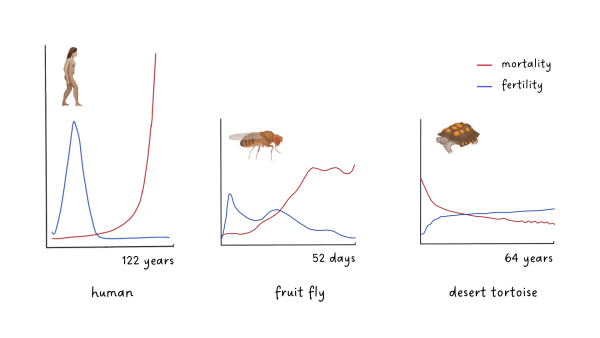

As much as I like music, I’m more of a listener than a maker. But luckily, one of my best friends, Imperial PhD student Jamie Mathews, is a music producer with a particular talent for electronic composition. I sent him a few animals, and he worked his magic with the sound design, programming unique settings for each animal based on their ageing patterns. First, he sped up or slowed down the audio relative to the animal’s lifespan, resulting in a chipmunk-like speed for the shorter-lived fruit fly, and a slow, rolling rumble for the immortal hydra. He then applied a distortion effect to represent the decay associated with ageing, and finally a reverb effect that multiplied the sound in accordance with the animal’s fertility rate. Festival-goers would get the chance to sing a snippet of a tune of their choice into our “lifespan emulator” (an MPC sampler), and see how their “tape of life” would play and decay for each animal.

With a solid, workable idea, and a successful Green Man application, we needed to source some funding for this activity to bring it to life. Luckily, there are a few pots of money available for public engagement activities, and we were able to successfully apply for funding from the Society for Experimental Biology, the Imperial Societal Engagement Seed Fund, and my own PhD funders, the GW4 MRC BioMed DTP – generous contributions which fully covered all costs for the stall.

The weeks leading up to the festival were spent painting props, sorting out practical considerations like van hire and equipment rental, and assembling a crew. To act as facilitators on the stall over the weekend, I looped in fellow biology PhD students Benito Wainwright, Amaia Alcalde Antón (who also contributed the beautiful animal illustrations for the stall, pictured above), and Josie McPherson, as well as psychology PhD student and invaluable “man with van” Conall Monaghan.

Thanks to this brilliant crew, the stall was an overwhelming success. Over the course of the weekend, we had hundreds of people pile into our tent, try their hand at some karaoke, and listen as their voices were warped and distorted beyond recognition. We had renditions of Otis Redding, Chaka Khan – and of course, for those stuck for a song choice, about a hundred versions of “Happy Birthday” – all deteriorating into chaos, stretching and compressing to mirror the lifespan of species across the animal kingdom.

The musical activity prompted some very chin-stroking conversations with adult festival-goers about whether or not it would be a good thing if we managed to extend human lifespan. The “no” contingent won out in the end, citing fears about limited resources, concentration of power, and the need for a natural end to bring meaning to life – but the yeses were a close second, arguing for the extra time spent with loved ones, and the diversity of experiences a longer life would bring.

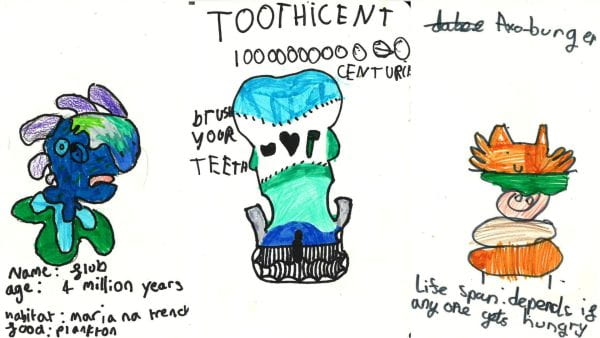

The kids were less concerned about the ethical ramifications of a longer lifespan, and instead deeply concerned with mashing as many buttons on the “lifespan-emulator” as their small fingers would allow. We had a whole host of wunderkind DJs chopping up beats that the festival headliners could only dream of, and this enthusiasm for the musical activity translated brilliantly into engagement with our learning outcomes. I was amazed at how quickly kids as young as five began to match what they were hearing from the sampler to differences in ageing, guessing at the longest-lived animals and dragging their friends over to explain what they’d just found out. Perhaps best of all was the wonderful creativity in our drawing prompt, where we encouraged kids to make up their own species and assign it a lifespan. Some of these would put even Ming to shame.

It’s hard to know who had a better time: us or the kids. Getting to talk about my research to so many people, on so many different levels, was an incredible experience; and it was made all the better by the festival atmosphere and the promise of post-stall music to catch. It was some of the most fun of my life, and I would absolutely do it again, even if it meant listening to a hundred more Happy Birthdays – though perhaps not quite 507.

To find out more about The Tape of Life, visit our Instagram @tapeoflifespan.