This year, to celebrate 100 years of postgraduate research at the University of Bristol, we’ll be sharing some of the fascinating stories uncovered by our team of research interns.

In this post, Dr James Watts, a recent PhD graduate in History and Assistant Teacher in the Department of History and the School of Modern Languages, tells a tale of apples, alcohol and agricultural research.

When we think of cider, we think of the West Country, but you might not realise that early research conducted at the University of Bristol is also part of the story of cider’s links to the region.

During the 1920s and 30s much of the research conducted by students at the University of Bristol had links to the key industry and agriculture that were crucial to the region, from cheese production to apple cultivation. Some of this research was undertaken by women and international students at Bristol, pioneering explorations into agriculture, from lichen, to stilton, to apples.

I have been involved in a project led by the Associate Pro Vice Chancellor in partnership with the Brigstow Institute and Bristol Doctoral College to explore some of the earliest PhDs at the university. During this time, it became apparent that Long Ashton Research Station (LARS) was a hub of research in the city as well as globally. LARS attracted international researchers interested in its pioneering research into fruit growing and it was this combination of the local and distinctive in West Country cider and the global in Indian students during British imperial rule that intrigued me about LARS.

Long Ashton Research Station and University of Bristol PGRs

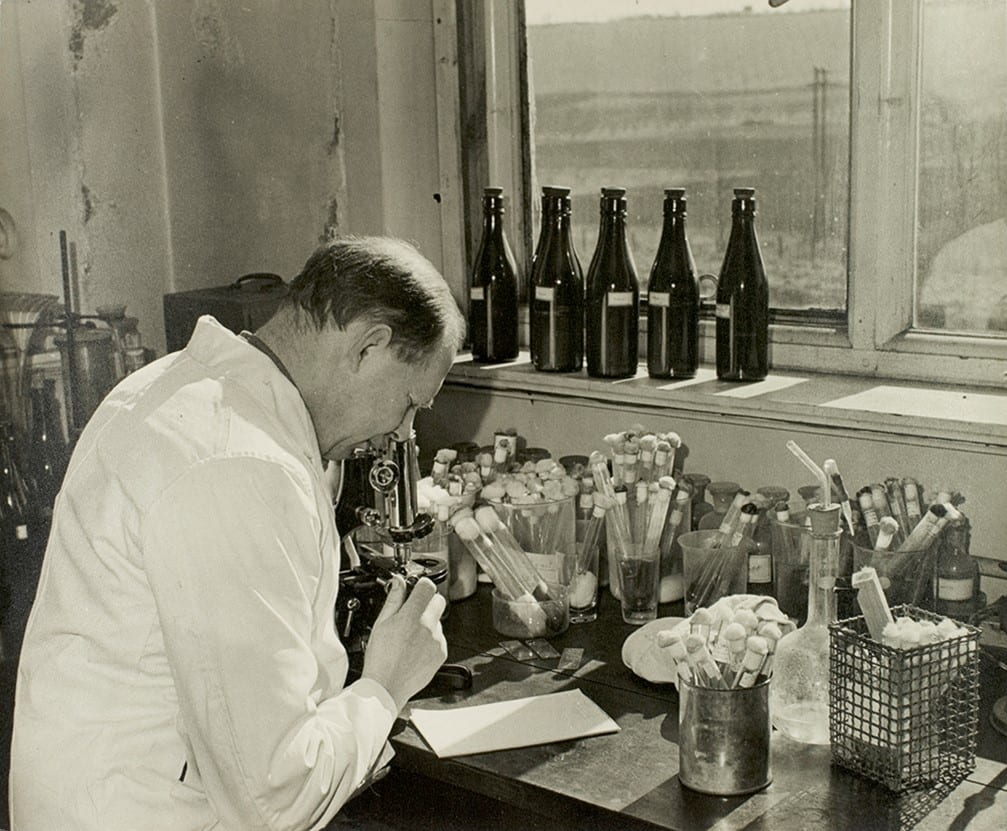

One area of research which PGRs and faculty collaborated on in the 1930s was in the botanical and agricultural work done at Long Ashton Research Station (LARS). The combination of alcohol, research, and local innovation is an intriguing insight into early collaborative efforts by the University.

There was a longstanding connection between LARS and the University of Bristol. The Station was set up with the help of the Smyth family of Ashton Court in 1903 to aid the growing of apples and the production of cider in the West Country. It was then incorporated into the University’s Department of Agricultural and Horticultural Research in 1912. Researchers such as Katherine Johnstone and Elsie Stella Smyth (a distant relation to the family at Ashton Court) worked at the research station during and after their PhDs. in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Johnstone worked on the resistance of apples to disease and Smyth examined peltigera, a lichen, and its effects on water, carbon dioxide and respiration. The close trajectory of the PhDs of these two women is suggestive of how mutual support and friendship was often vital to women in research. Smyth later married Thomas Wallace, the director at the station and Professor of Agricultural Chemistry at the University of Bristol.

The station had a strong international cohort, especially with its PGRs, and 6 Indian students in the 1930s worked at the station. Indian students have a particularly long tradition in Britain, with figures such as Mohandas Gandhi studying here, and these imperial links were very much in evidence at LARS as well.

In Bristol, their main focus during the interwar years was with the growing of apple trees. Students such as Sham Singh from the Punjab, Gurunjappa Siddappa who did his BA in Madras before coming to Bristol, and Yelsetti Venkoba Rao in the 1930s, became particularly interested in rootstocks and the practice of splicing and grafting older trees onto younger trees so that they could bear fruit more quickly. Siddappa’s research focused on the links between soil quality and the composition of dried peas. There was also collaboration between students and staff and PGRs like Vishwanath Govind Vaidya published an article with Thomas Wallace in 1938 on the manuring of strawberries. These interests, and the presence of these students, speak to imperial links, as well as colonial development policies in the 1930s. But it also emphasises the recurrent concern over food and agriculture in India with famine under British rule occurring in the 1890s, during these student’s doctorates in the 1930s, and during the Second World War.

In the interwar period there was an annual open day at LARS where the experiments in fruit growing and cider making were exhibited. This was noted in top research journals like Nature, which commented in 1937 on the experimentation with German yeasts and the focus on non-alcoholic fruit juices made from syrup which the station had advanced.

During the Second World War the supply of oranges was threatened, and as a response the station developed Ribena as a homegrown alternative using blackcurrants to provide Vitamin C. Numerous PhDs considering food, from cheddar and stilton, to potatoes and apples had links with the station which allowed practical experiments to be undertaken on the growing of food.

The importance of the research into apples and cider remains pertinent and Somerset is, along with Herefordshire, the biggest cider producing area in the UK. Some Cider apple varieties, including some 29 known as ‘The Girls’, were tied to the research centre. After its closure in 2003, the pedigree of these were lost until a paper in 2020 which recovered these apple varieties. Goldney Orchard, originally planted in the 1700s, preserves some of these apple varieties like Nonpareil and golden pippin where, even through lockdown, students and staff use them for cooking and, of course, to make cider. There is also a project beginning in Autumn 2021 led by Professor Keith Richards into certain species of Long Ashton cider apples at the Goldney orchard, as well as identifying apple types across the South-West.

The work of LARS, and many similar institutes form part of the story of the global ‘green revolution’ allowing us to feed and support, however unsustainably, a planet of 7.8 billion. It is also part of South West Britain’s success in making world-famous cider and shows some of the direct applications of university research.

As a student at Bristol University from 1972 to 1975 I remember obtaining industrial quantities of cider from Long Ashton Research Station for our parties!