This year, to celebrate 100 years of postgraduate research at the University of Bristol, we’ll be sharing some of the fascinating stories uncovered by our team of research interns.

In this post, Lena Ferriday, a postgraduate research student in the Department of History, explores the links between her own work and avid caver and alumnus Leo Palmer.

The University of Bristol Speleological Society (UBSS) celebrated its centenary in 2019, making it both the oldest society at the University, and the oldest University caving club in the world.

The Society was founded by members of the Bristol Speleological Research Society. In 1919, these members undertook a dig at Aveline’s Hole, a cave in the Mendips, under the leadership of physics student Lionel Palmer, affectionately known as Leo by his peers. The excavations at Aveline’s were significant, leading to the formation of UBSS and continuing to form an important part of the Society’s current museum collections.

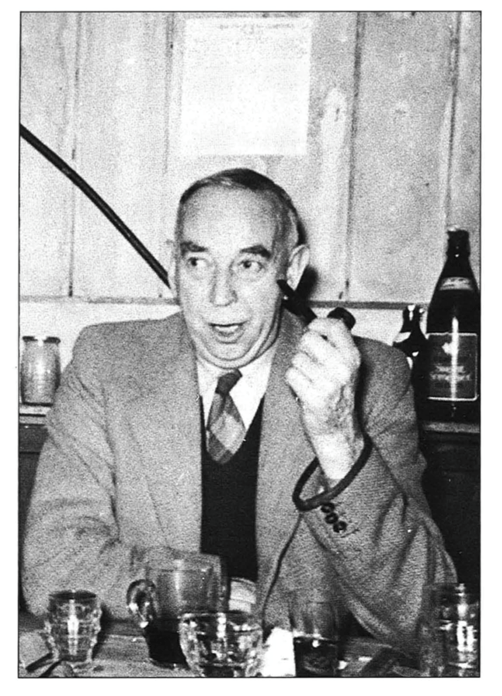

Two years later, Palmer became the first student to be awarded a Ph.D. in Physics at the University of Bristol. Taking up a lectureship in Electrical Engineering at the University of Manchester in 1923, and later a professorship in Physics at the University of Hull, Palmer continued to publish research in these fields throughout his life. Yet his love of caving kept his academic interests broad, and he contributed important research to the fields of geology and archaeology.

As an environmental historian, it is at this point that my own research intersects most closely with that of Palmer. My work resides at the intersection of material and cultural environmental histories, considering the relationship between the cultural perception of landscapes with the bodily experience of existing within them, while Palmer’s focus was on the physicality of the environment.

However, Palmer’s close in-person engagement with the sites he studied, in the tradition of speleological research, is interestingly positioned in close-proximity with my own academic aims to employ practice-based research methodologies, to engage more closely with the embodied experiences provided by landscapes both in the past and present.

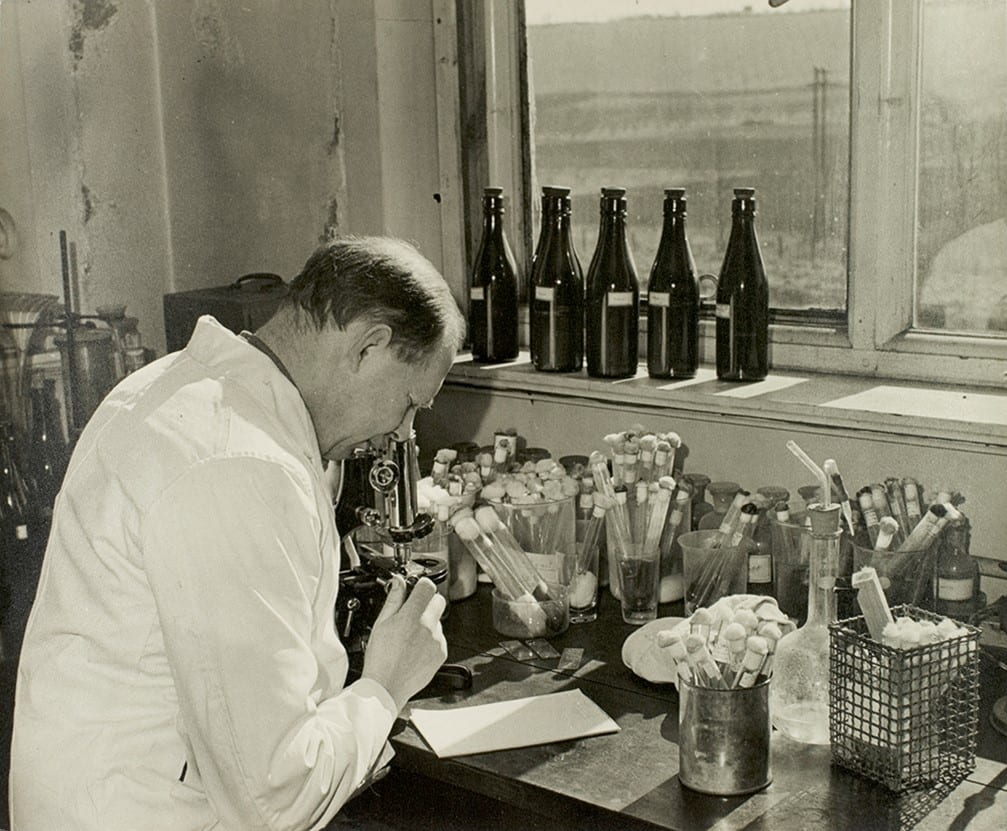

Palmer’s quest to engage with research across these fields was innovative and inspiring, and led to the publication of a great deal of valuable research. He promoted active scientific research amongst the student members of the UBSS, and established a journal for this work to be published in. The UBSS Proceedings continues to run as a well-regarded peer-viewed journal, within which I have had the pleasure of publishing a co-authored piece of historical research. The paper explores oral testimonies from members of the Society, considering particularly participants sensual and embodied engagements with subterranean environments.

Interestingly, I think the publication of this piece, the first of its kind in the Proceedings, has continued the legacy of Palmer’s interdisciplinary inclinations even further beyond the boundaries of scientific and caving based research. Whilst not an historian by profession, Palmer’s interdisciplinary inclinations and drive for producing and saving academic knowledge have led to a great number of overlaps with my own historical work, both through the researching of his life for this project, and my research into the history of the UBSS and the embodied memories of cavers.

Palmer’s interdisciplinary interests were united in 1938, when he oversaw a pioneering geoelectrical survey at the Mendip cave Lamb Leer Cavern, which revealed the existence of a second large chamber close to the already discovered Great Chamber in the cave.

In 1956, Palmer returned to Lamb Leer with the improved equipment of a ‘Megger Earth Tester’, to test ground resistance, which he obtained through a £230 grant from the Royal Society. As a result, he confidently estimated the position of the chamber. Yet despite attempts to find the now named ‘Palmer’s Chamber’, it has still not been found, and research by Butcher, et al in 2007 has highlighted errors in Palmer’s original interpretation.

In 1957, Palmer’s interdisciplinary interests fully converged, climaxing in the publication of Man’s Journey Through Time: A First Step in Physical and Cultural Anthropochronology, and he began to conduct research along similar lines to my consideration of both the physical and cultural attributes of the environment.

Palmer also sought to obtain the first of a number of rooms for the Society to house its museum and library collections in 1919, on the site of the former Officers’ Training Corps ammunition storeroom between Woodland and University Roads, before the exponential growth of the collection incited its move to first the Lewis Fry Tower and then the ground floor of what is now the University of Bristol’s Geography Department in 1927.

Again, his love of active research ensured that the collections held by UBSS remain large. Palmer’s efforts with the UBSS have helped the preservation of important archival material which continues to be accessed by geologists, archaeologists and the occasional historian. His desires for preserving material for posterity led him to his later career as Curator of the Wells and Mendip Museum, a position to which he was appointed in 1954.

The research project from which my Proceedings paper emerged, led by the Department of History’s Dr Andy Flack in 2019, sought to indirectly continue the conscious preservation of UBSS material that Palmer initiated. Here, however, instead of protecting physical traces of cave landscapes, we protected the memories of these spaces. Across twenty oral history interviews, our participants shared memories of the society, the social life of caving, and their experiences of travelling underground.

The UBSS archive has thus been extended into the digital realm, with these interviews recorded and transcribed into an accessible database, and with the hope that other societies might undertake similar work to preserve their human histories, and the human histories of the subterranean, alongside their physical ephemera.

For more information on the research into the history of UBSS, see this 2019 Epigram article.

You can find out more about Lena Ferriday’s work by reading her research profile, or by following her on Twitter.