This guest blogpost is a personal reflection by Adeela ahmed Shafi, a PhD candidate in the School of Education. Adeela is also Senior Lecturer in Education at the University of Gloucestershire and Vice-Chair of the Avon & Somerset Police Powers Scrutiny Panel.

If you’re a researcher, there’s plenty of literature available on how to be ethical; how to reflect and acknowledge your presence in research, in terms of research design, data collection, analysis and indeed the claims made.

However, there’s not much out there on how the research process actually impacts on the researcher.

My research contributes to the intense political debate on youth justice by exploring the nature of disengagement in young offenders in a secure custodial setting and how this group can be re-engaged.

What I would like to do here, though, is talk about the challenges — methodological, ethical and personal — that I needed to navigate in order to get to the findings.

Challenges, dilemmas and adapting your approach

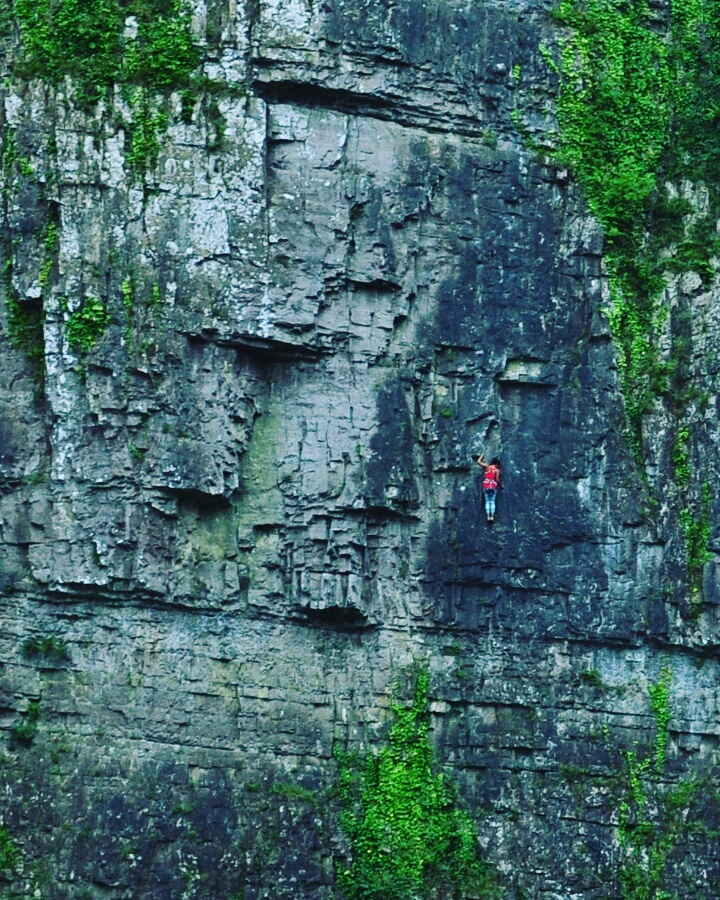

For me, there were many personal and methodological challenges in working with incarcerated young offenders.

For example, I had prepared all manner of interview aids to help me elicit data from my participants — all derived from the literature in terms of the best way to interview children and vulnerable participants. However, I ultimately found that these were all quite superfluous and in themselves made many assumptions about my participants.

In the end, then, I found I had to ditch these and just use myself as the main resource. This involved having to reveal some of my own vulnerabilities and weaknesses, and in doing so redress the power imbalance between myself as a researcher and the incarcerated participants, who had very little power or autonomy. I hadn’t actually planned that in my data collection prep work!

Having got myself in a position where my participants were willing to trust me and open up, I felt myself amidst an array of ethical challenges and dilemmas. Not least of these was that I was now in a privileged but weighty position of responsibility, with a duty to tell the story of a ‘doubly vulnerable’ group who had little voice in a society that had already passed judgement on them.

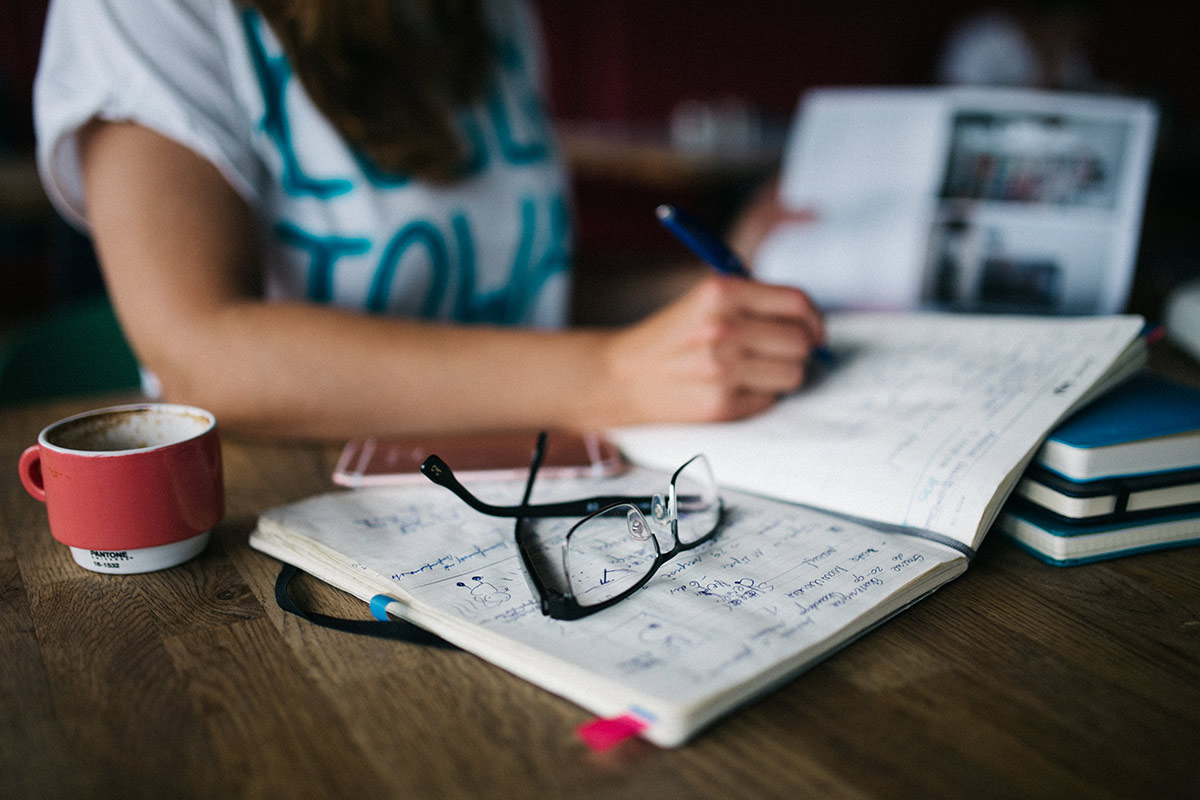

Retaining and representing what’s been shared

Because of this sense of responsibility, I felt that the handling of the data had to avoid fracturing the essence of what had been shared. I found my memory, emotions and the field notes of each interview were essential in this, because I could recall the additional aspects of the interview not recorded in transcriptions to enter the analysis — in particular, the body language and the atmosphere in the room during the interviews. Even now as I write this, I find myself transported back, and I remember how riveted I felt when listening to them.

My experiences also reinforced the criticality of the researcher in the generation of data, and in ensuring that this data was represented in a way that captured the richness of it. I didn’t see it as data ‘waiting to be gathered’, because my participants indicated they’d never had the space to give thought to their educational experiences in the way that engagement with the research had enabled them.

In short, working with these young people meant I was able to get a glimpse of their potential.

But I feel guilty.

In participating in the research, I was showing these vulnerable participants what could be — but what was not to be. Being unable to facilitate the potential I witnessed beyond the scope of my research stung.

I realised then that research can change you.