Since its inception, our annual Research without Borders festival has been an opportunity for Bristol’s postgraduate researchers to set aside familiar communication formats like posters and PowerPoint presentations, and to consider how they can share their pioneering projects using methods that are a bit more … ‘outside of the box’.

When this year’s Research without Borders exhibition had to be cancelled due the COVID-19 pandemic, it seemed that May 2020 would come and go without us being able to put the spotlight on any inspired and imaginative displays of PGR research. However, the BDC team had an idea: what if we devised a challenge that encouraged PGRs to find crafty and creative ways to tell the story of their research — with scope to use everyday materials from around the house?

The result was our first-ever Research without Borders ‘virtual showcase’ competition — and, below, you can take a self-guided tour of all 22 exhibits. We hope you agree that the entries are as ingenious as they are entertaining, and that all of the PGRs who participated deserve a huge amount of credit (and thanks) for taking the time and effort to create such compelling project pics.

We’d also like to thank our competition judges: Professor Robert Bickers (Associate Pro Vice-Chancellor, PGR), Sarah Bostock (Head of Marketing) and Doctor Jen Grove (Public Engagement Associate). You can read their comments on the winning entries by scrolling to the end of the page — although we’d recommend that you take the full tour.

Virtual showcase ‘exhibitors’

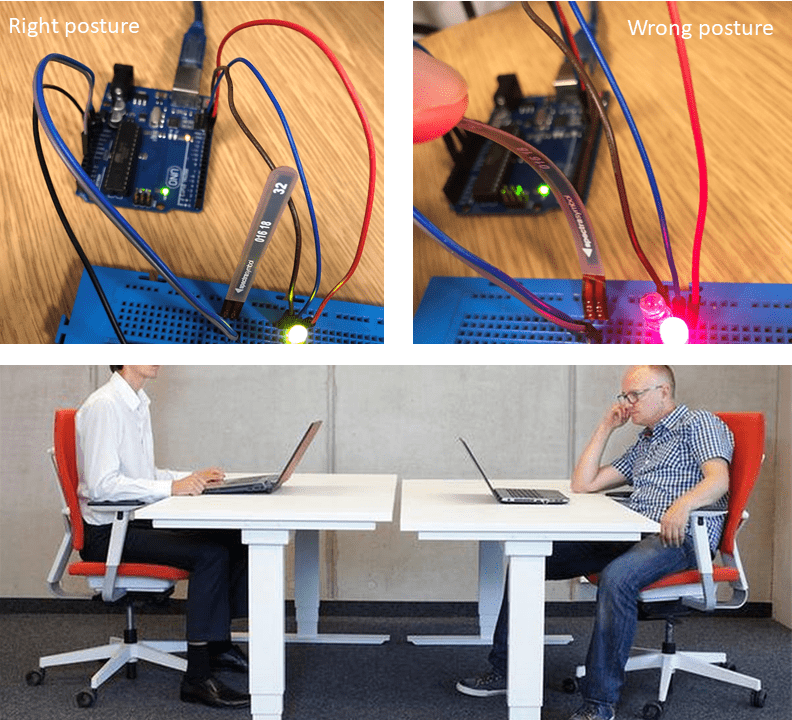

Khalid Al Mallak and Sarmad Ozan,

School of Computer Science, Electrical and Electronic Engineering and Engineering Maths

Can you sit normally on your chair without slouching or leaning forward?

Working in an office or from home has the disadvantage of sitting for prolonged periods. Therefore, to maintain our correct posture, we built a device that detects any improper lean to our posture while we are sitting to perform our work and notifies us with a light indicator. By keeping the right posture of our bodies, we would protect our necks, shoulders and lower back from getting exhausted.

Merihan Alhafnawi,

School of Civil, Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering

Using a swarm of robots can be more efficient than using just one robot in applications like firefighting missions and environmental monitoring. A human interacting with one robot sounds complicated enough, so how about interacting with 100 robots? “Expressive swarms” researches how humans can interact with a whole swarm of robots! If the robots can work together to express themselves in an intuitive and meaningful way to the humans, then the interactions become natural, almost like working with a friend.

Lujain Alsadder, Bristol Medical School

Remodelling from different perspectives: what the heart can tell us?

Blockage of a coronary artery will deprive certain areas of the hearts from oxygen and nutrients, leading to cells death and substantial changes, known as remodelling, in structure, function and integrity of the heart. My research explores ongoing remodelling which involves cellular components like mitochondria, and major constituents including heart proteins, as well as regional and blood metabolites. The aim of my work is pinpoint key changes to better understanding the process of heart remodelling and identify possible therapeutic targets.

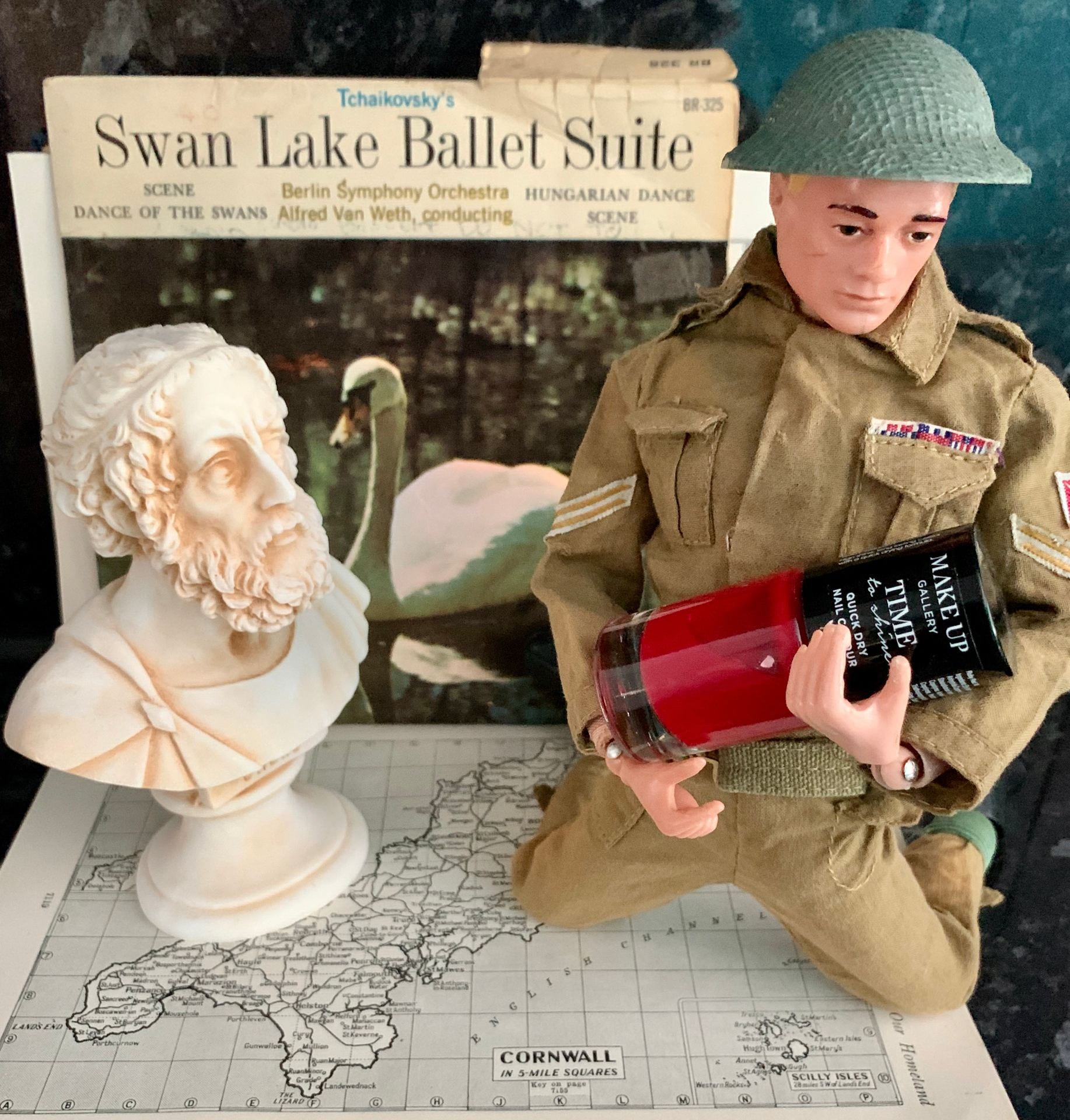

Linda Bassett, School of Humanities

‘Nothing Like a Dame’: Womanhood and Feminine Experience in the Work of Laura Knight

Today a forgotten name of Art History, Laura Knight was a pioneering artist. Her paintings from the first half of the 20th century chart the progressive role of women through a period of social and cultural change. Her sophisticated images rely on familiar subjects, yet confront traditional stereotypes and challenge the attitudes of the time. Still relevant in our modern age, Knight’s work deserves a reappraisal.

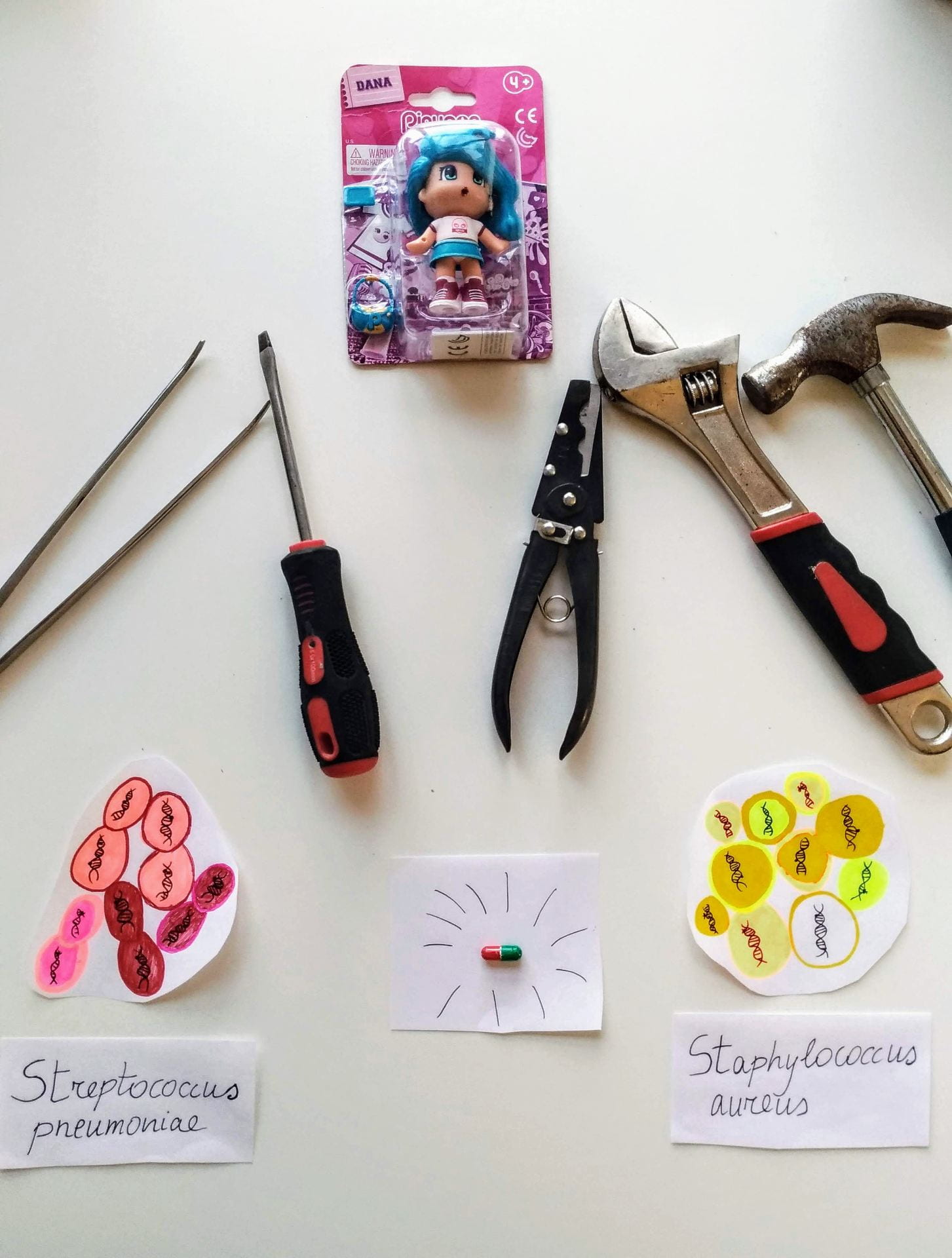

Dora Bonini, School of Cellular and Molecular Medicine

Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus are two dangerous bacteria, causing high mortality worldwide. They are resistant to antibiotics and we need new drugs to treat them. They have several molecular “tools” that allow them to attack humans. Both bacteria include a variety of subgroups, with differences in their DNA. Some subgroups are better than others at attacking humans. My research wants to find the DNA differences between groups, understand why they make some groups more successful and target them to make new antibiotics.

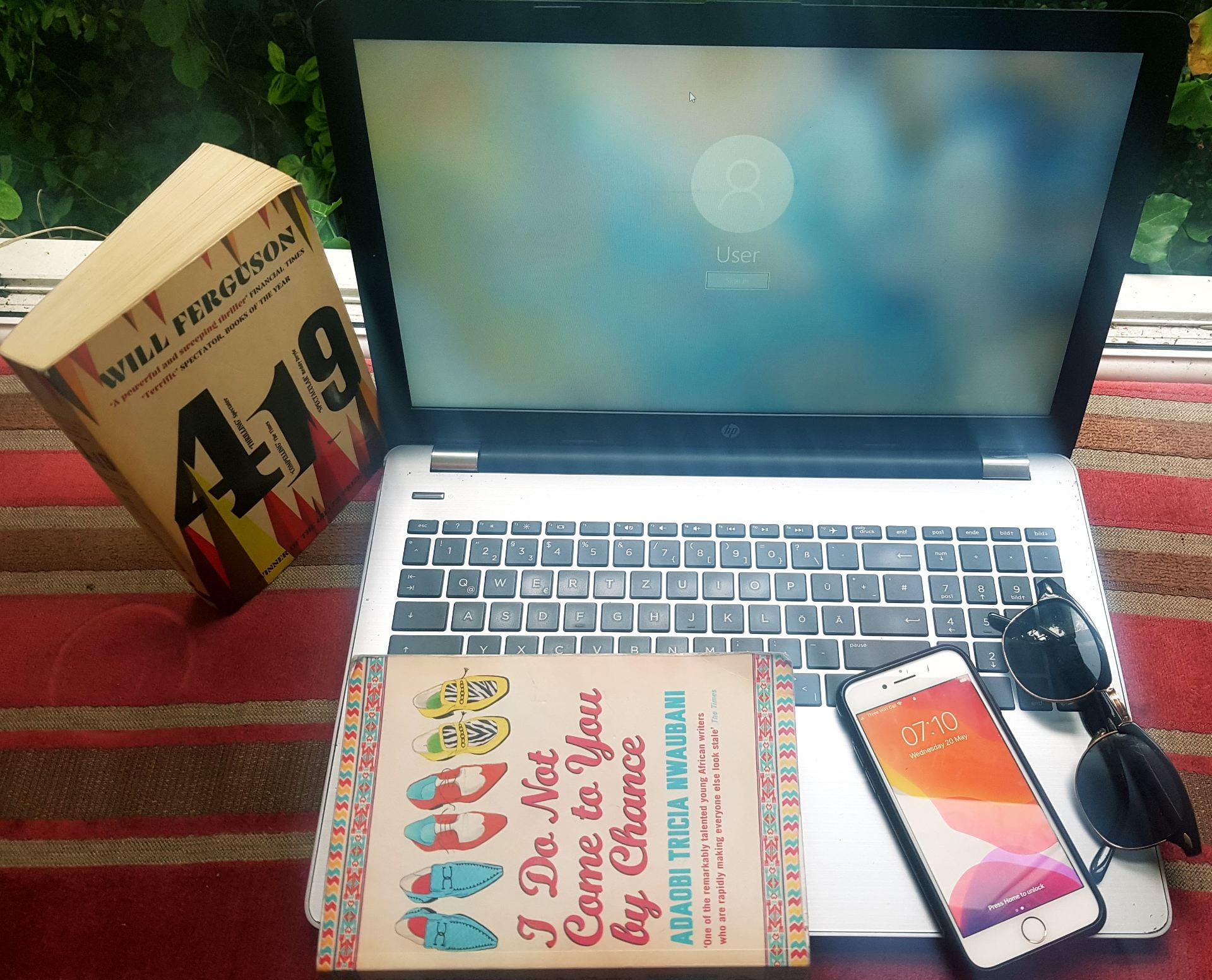

Daniel Chukwuemeka, School of Humanities

That African Prince That Keeps Sending You E-mails: E-fraud Economy in Postcolonial Nigeria

Internet fraud is a global digital practice, yet Nigeria is one country that is nearly generally associated with e-fraud by a greater number of people. My research explains the reason behind this collective assumption: the exchanges that obtain in fraudulent transactions are similar to the political and economic exchanges that constitute the Nigerian state; just as the scammer impersonates a real character, Nigerian government officials hide behind state legitimacy to convert public wealth to private use.

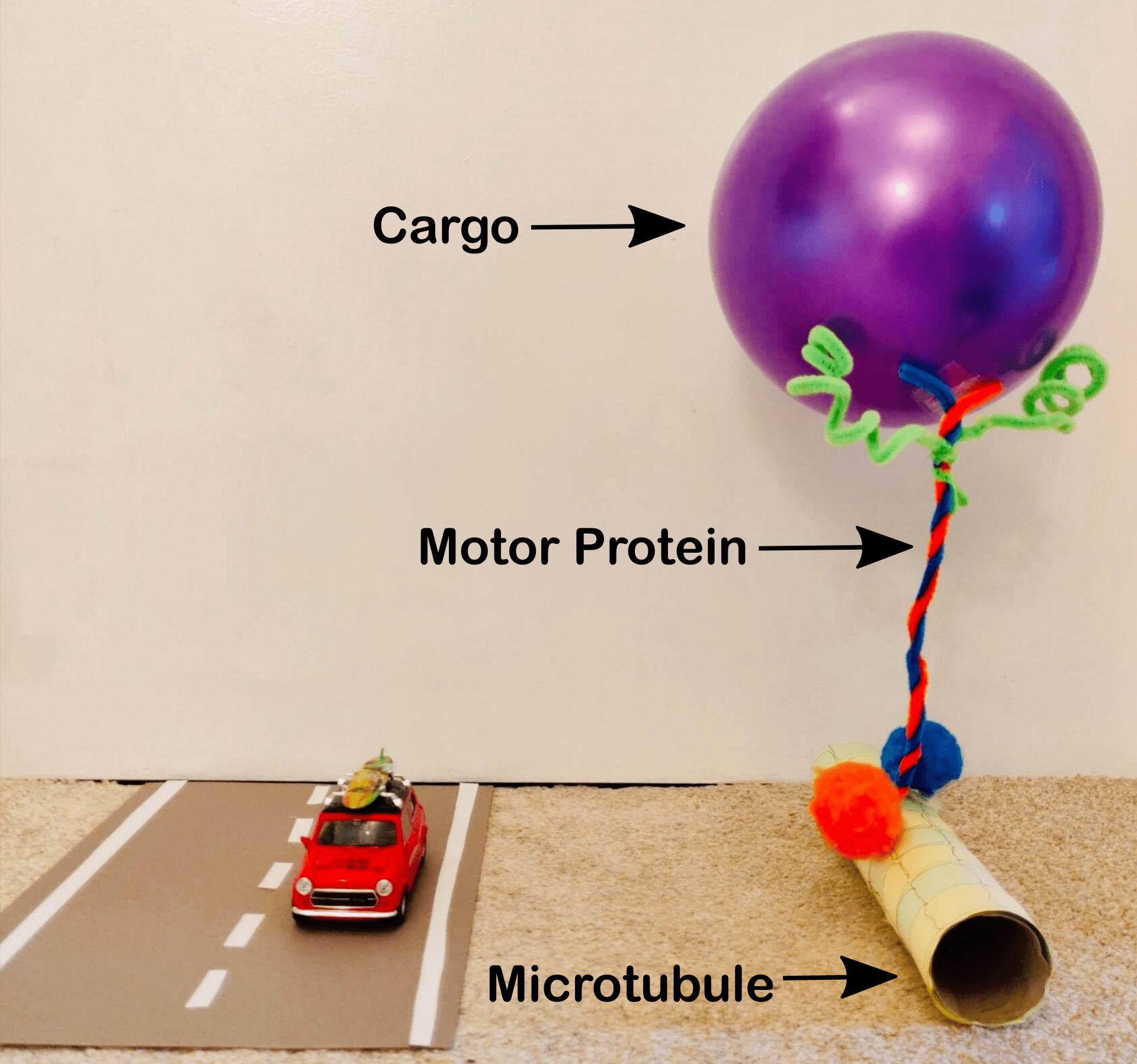

Jessica Cross, School of Chemistry

Cells and the City: Driving Transport in the Cell

Just like our cities, inside our cells things are constantly in motion. Careful control over these transport processes is essential for us to stay healthy. The “roads” are a network of filaments called microtubules and the “cars” are motor proteins which pick up their cargo and walk along the tracks to deliver them to their destinations. We are developing new tools to ‘drive’ these motor proteins when they go wrong in human diseases.

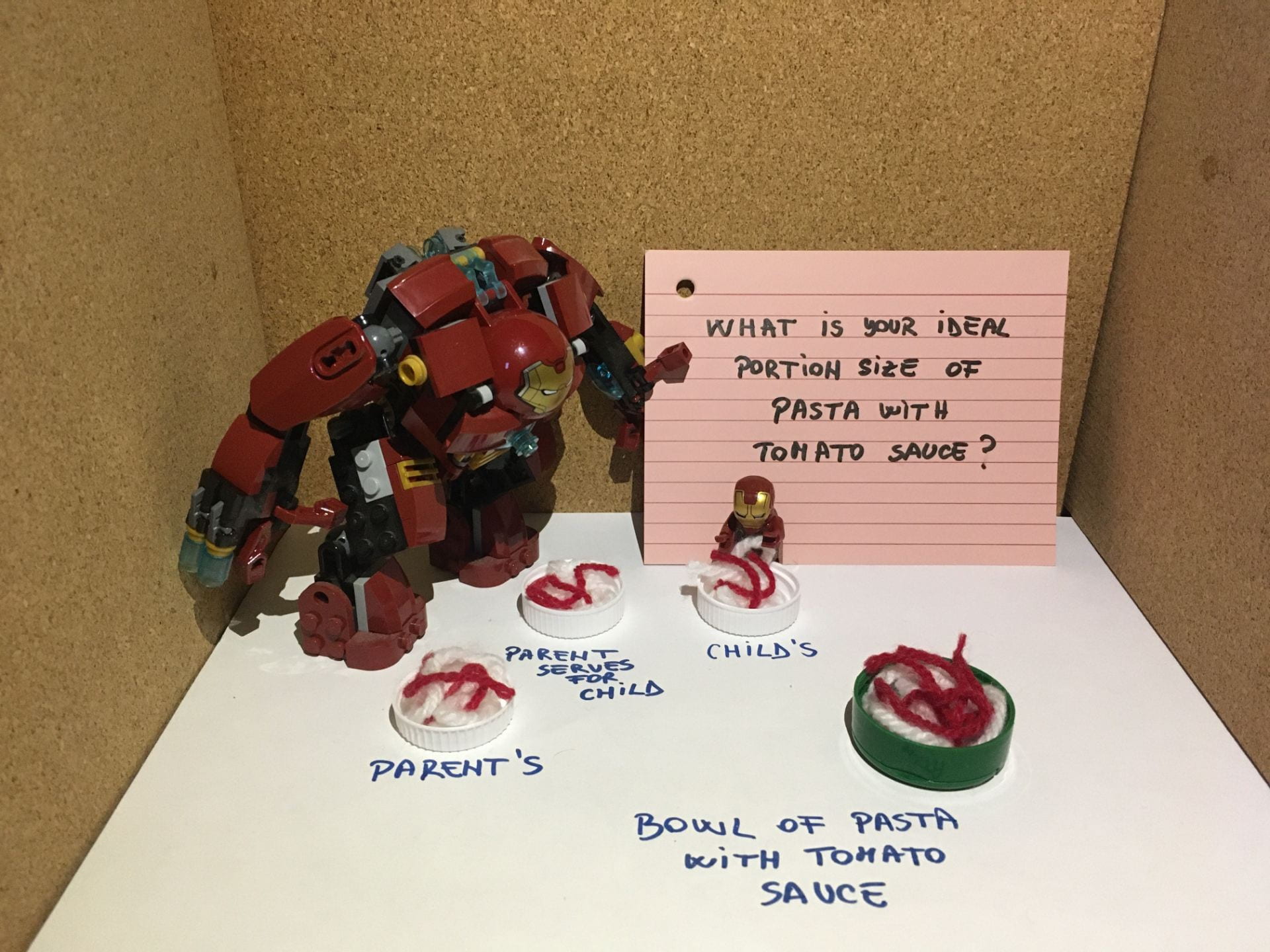

Anca Dobrescu, School of Psychological Science

Exploring the associations between parent’s ideal portion size, the amount a parent serves their child and child’s self- selected portion size

In the first few years of their life, children are dependent on their parents to offer them food. However, parents are given little sex- and age-appropriate guidance about the portion size of food suitable for children. Parents report using estimates of their own portions of food when deciding how much to offer their children. As a result, we predict that the amount parents serve themselves is correlated with how much food they serve their children and with the amount children self-select. Understanding these associations will help support parents, and provide new insights into the prevention of childhood obesity.

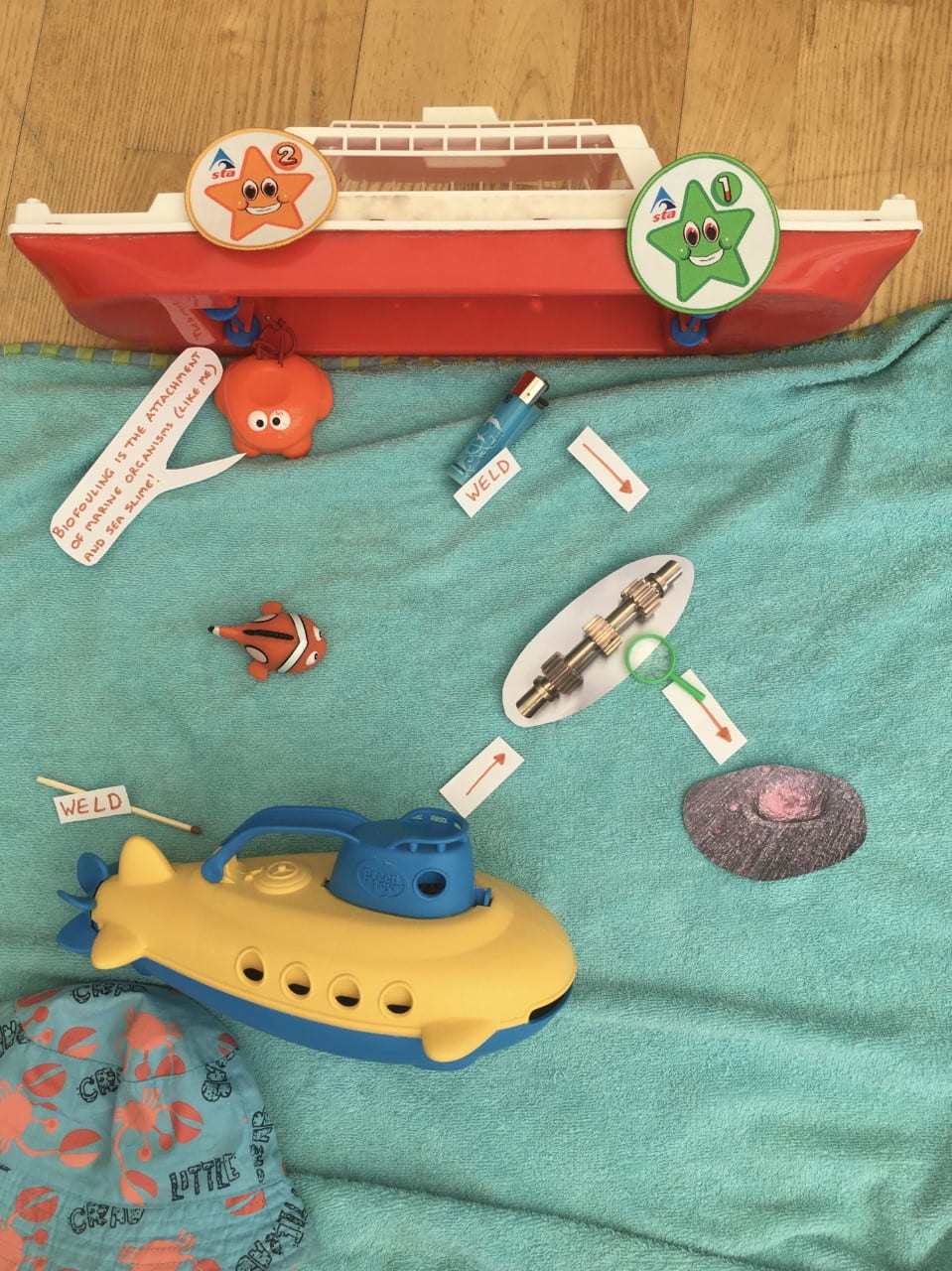

Tamsin Dobson,

School of Civil, Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering

Hot, Wet, Slimy and Broken

Your submarine is sinking because a part has failed where it was previously repaired by welding! Why did it fail? The weld? Corrosion? Biofouling? My research aims to answer these questions for a metal that is used extensively in submarines and ships: Nickel Aluminium Bronze. I weld the metal, use special microscopes to look at it, drop the metal into the ocean (and the lab) and then try to break it. I call it my “hot, wet, slimy and broken” method!

Isolde Glissenaar, School of Geographical Sciences

Mapping sea ice in a warming climate: how satellites measure sea ice thickness

This project uses data from satellites to study the thickness of sea ice. The satellites that we use shoot laser beams towards the surface of the sea ice and measure the time until the reflection of the beams return. Over time the satellite returns to the same location. If it takes longer for the reflection to return now, we know that the ice is thinner than before.

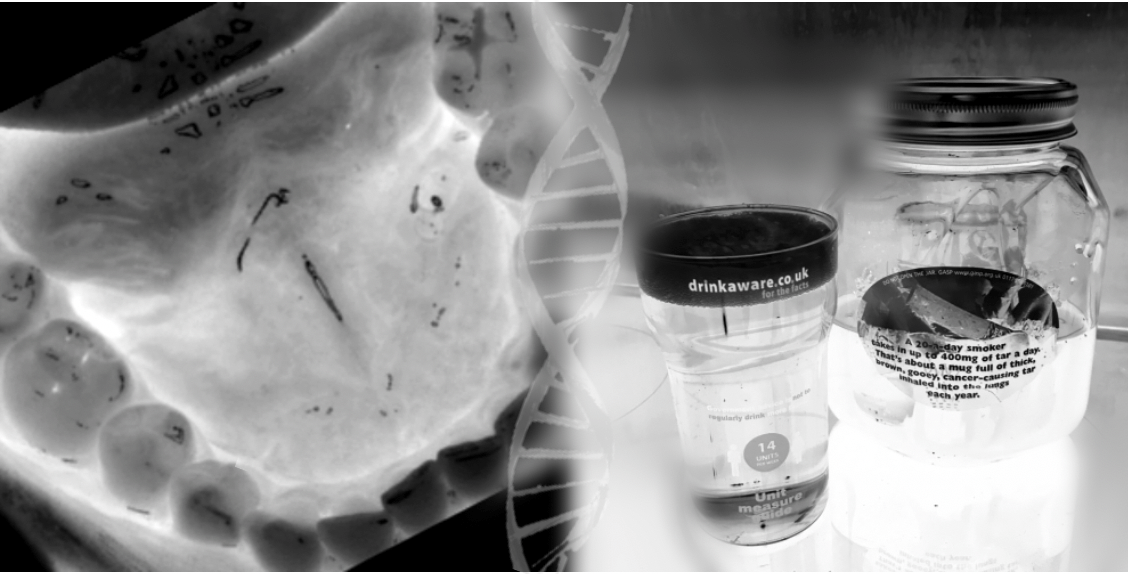

Mark Gormley, Bristol Medical School

Spotlight on Mouth Cancer

The world’s 6th most common cancer is found in the mouth and throat. This disease is predicted to increase by a third over the next 10 years. Known risk factors include cigarette smoking and alcohol, as well as the human papilloma virus, which is thought to be sexually transmitted. While the majority of cases of are linked to smoking and alcohol, using genetics we can better understand the contribution of less well known causes. My research analyses large genetic datasets of people with mouth and throat cancer and studies cell lines to identify new potential targets for prevention or therapy.

Eleanor Haines, School of Economics, Finance and Management

Root-ing for Community

How can Community Farms encourage people to engage more with the environment? Or to care for others in their community? This research examines how volunteering on a Community Farm can physically involve people producing their own food, helping us to think about where our food comes from, and its impact on the environment. It will explore how they can bring people in communities together, and form relationships between farmers and customers.

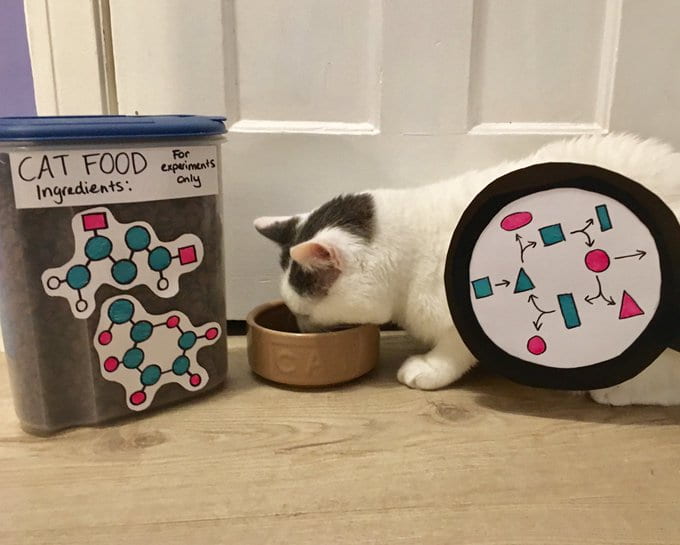

Amy Holt, School of Cellular and Molecular Medicine

Using labelled nutrients to understand cancer cell (or cat) metabolism

To find new ways to treat cancer, we need to know what makes cancer cells different from healthy cells. Like all living things, cancer cells (and cats) metabolise nutrients to survive and grow, but cancer cells do this differently to healthy cells. In the lab we can give cancer cells labelled nutrients, which allow us to ‘see’ how their metabolism is working. This can help to design new treatments, or to work out how to use existing treatments more effectively.

Hernaldo Mendoza Nava,

School of Civil, Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering

Bioinspired sound production using instabilities

The annoying sound of crushing a can or squeezing a plastic bottle is produced by buckling! Likewise, ermine moths buckle a striated membrane in their wings to produce distinctive sounds to ward off bats. In engineering, buckling can lead to structural failure but nature provides us examples of how to exploit it. This research takes inspiration in ermine moths to develop structures with adjustable acoustic and dynamic response to enhance the design of sensors and actuators.

Olivia Morris-Soper, School of Humanities

Magical Objects in the Medieval Period: Tools of Cunning Women, Seers and Sorceresses

This thesis explores connections between Arthurian magical women and their historical predecessors in Anglo-Saxon England. Magic and supernatural landscapes lie at the heart of Arthurian literature and there is a close connection between magic and Arthurian female characters. Anglo-Saxon cunning women were established magical practitioners and can be seen in the archaeological record. This project combines archaeology and literature to consider the similarities and differences between these women, thus shedding new light on British medieval magical women and their tools.

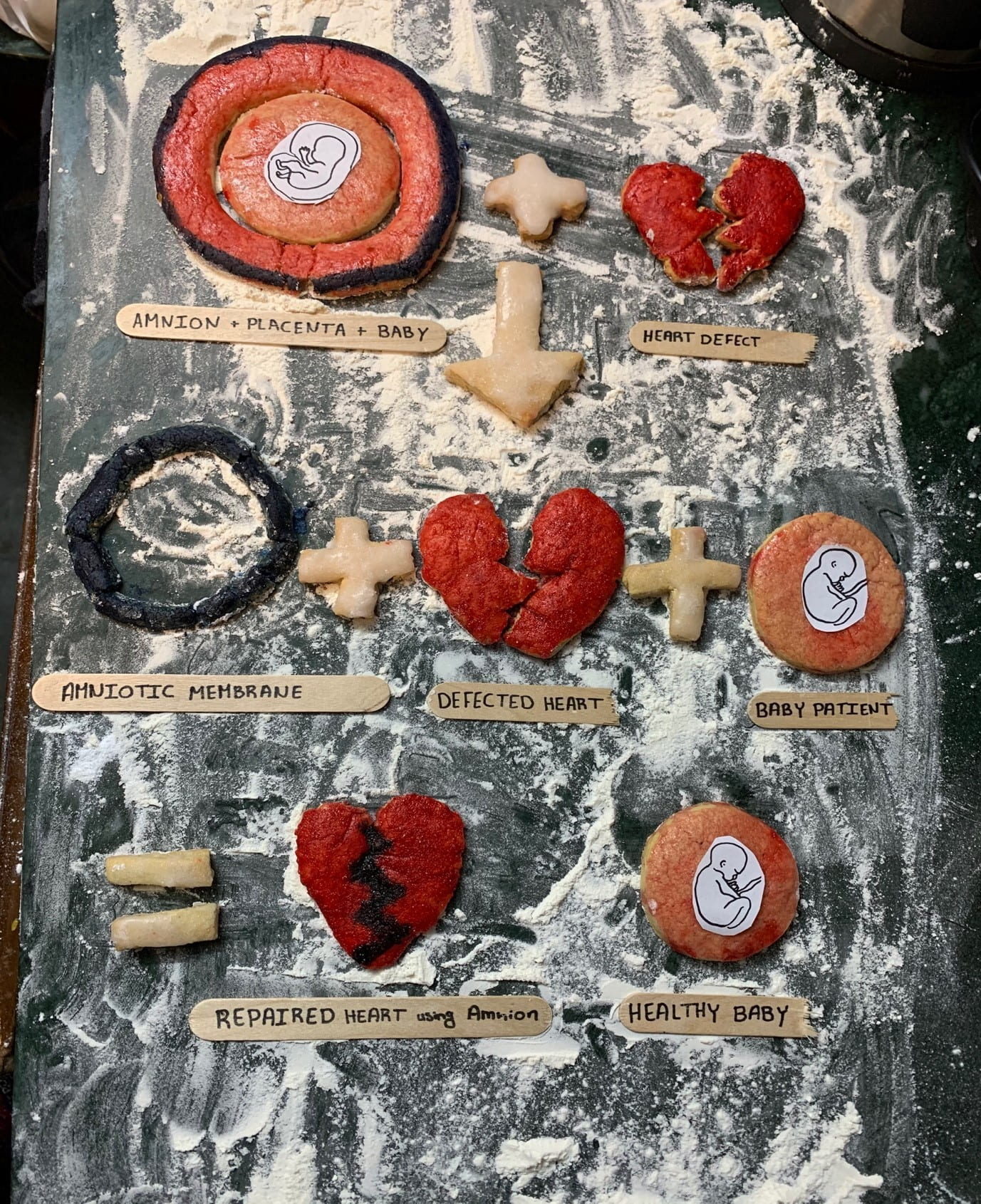

Shahd Mostafa, Bristol Medical School

Bio-Fabricating Constructs Suitable for Pulmonary Valve Replacement Therapy in Paediatric Patients with Congenital Heart Defect

Children born with a structural defect in their heart struggle to survive given the current procedures and repair methods that fail to grow with the child’s heart. Therefore, the child needs several open-heart surgeries throughout their life leading to increased death rates and a reduced life quality. To solve this issue, I obtain the amniotic membrane from the placenta, process it, and use it to fabricate a biomaterial that has the ability to grow along the child’s heart as well as encourage the heart to regenerate. This material would potentially eliminate the multi-step repair process since only one procedure is required to repair the heart, increasing the quality of life and survival of children born with congenital heart disease.

My Nguyen, School of Physics

How can we optimise membrane protein crystallisation?

The cell uses membrane proteins (MP), which are located at the cell surface, to communicate with their outside world. Studying MP structures can improve drug design and the diagnoses of many diseases. We determine the structure by shooting X-rays through MP crystals. Finding the right crystallisation conditions is like straying in a maze without a map. My research focusses on providing phase diagrams (PD) as ‘crystal maps’ to find the right crystallisation conditions.

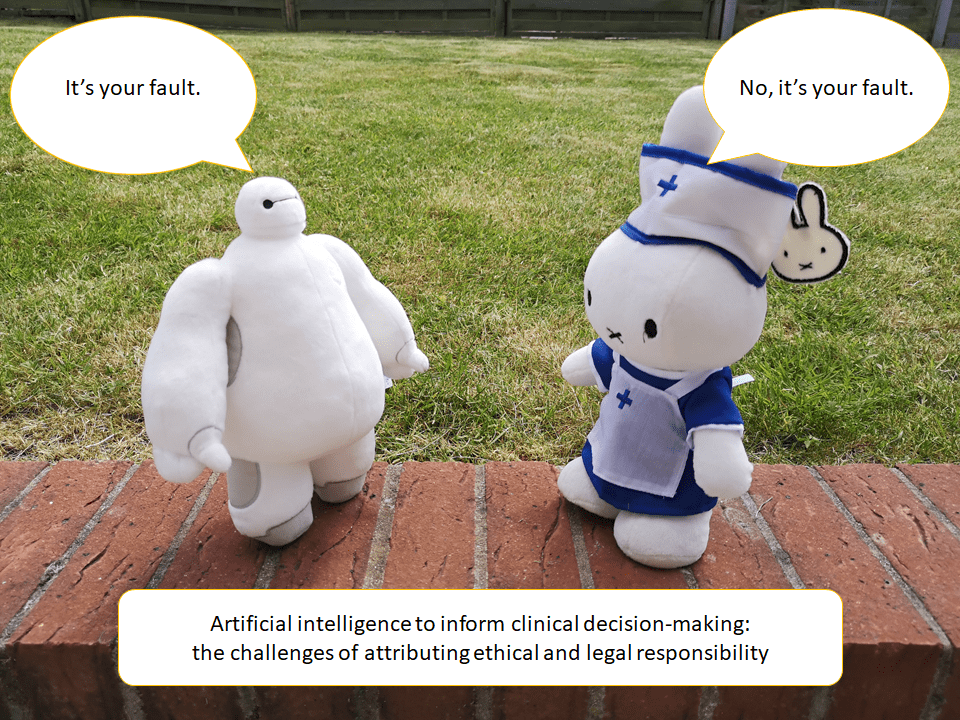

Helen Smith, Bristol Medical School

Artificially intelligent (AI) powered systems have been developed to aid clinical decision making; some have been deployed into healthcare. Determination of ethical and legal responsibility is necessary to ensure stakeholders are fully aware of their duties and obligations to patients, thus aiding the goal of preventing harmful consequences of AI use.

Alex Willcox, School of Physiology, Pharmacology & Neuroscience

Motor Adaptation allows us to adjust our movements in response to changes in our environment. However, with age, adaptation becomes slower and less effective- possibly explaining the increased incidence of trips and falls amongst older adults. By training rats to reach for a food reward, motor adaptation can be induced by a sideways shift in reward position. Alongside behavioural studies in humans, this rodent model is hoped to identify possible causes of the age-related decline of motor adaptation.

[Find out more about animal research at the University of Bristol.]

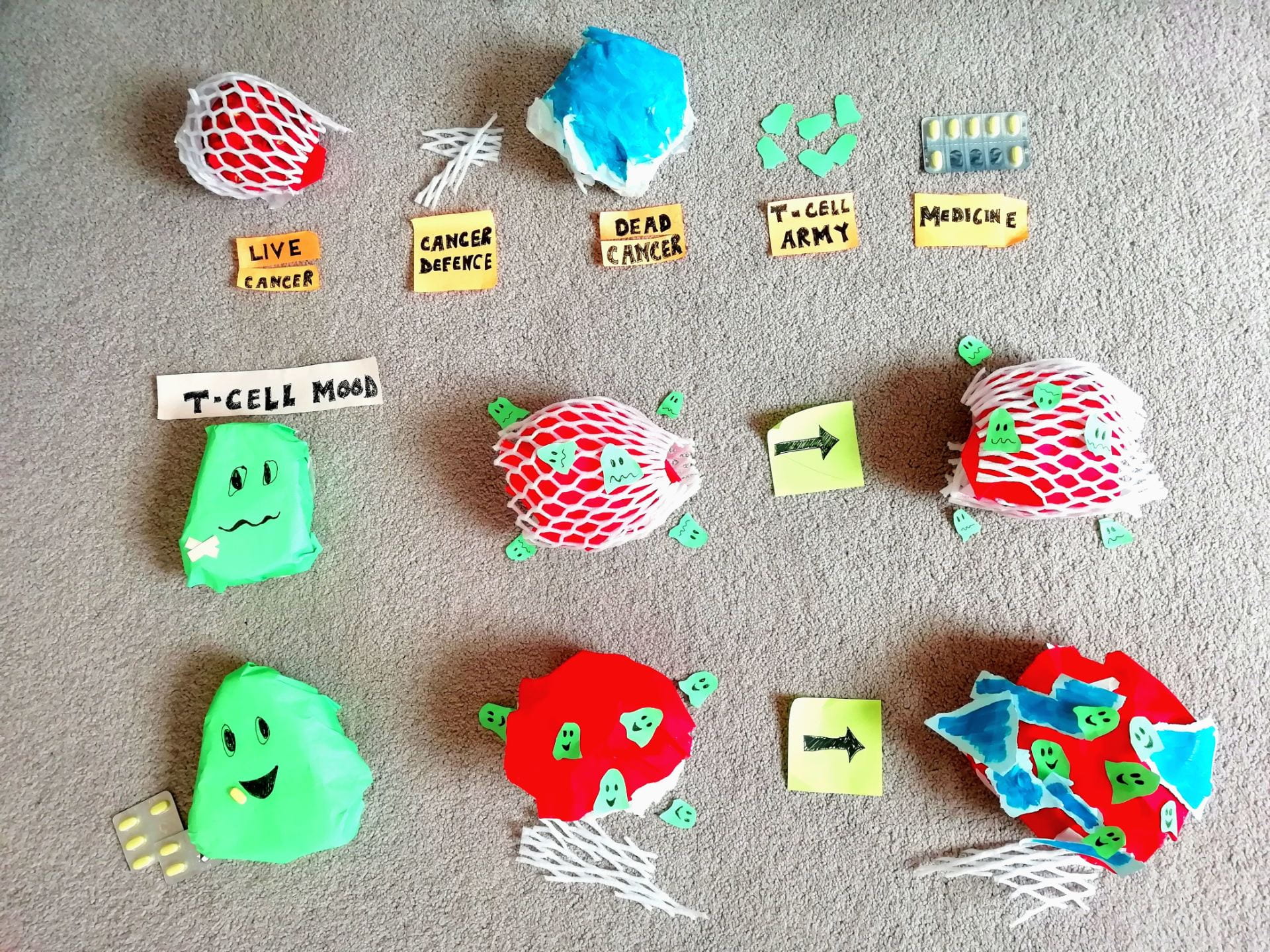

Carissa Wong, School of Cellular and Molecular Medicine

Boosting the immune system to shrink tumours

Cells: building blocks of our bodies,

Immune system cells protect us from disease,

Cancer happens to be one of these,

Key immune soldiers are called “T-cells”

Theoretically they can kill cancer pretty well.

But in a solid lump of cancer which we call a tumour,

Cancer cells have a malicious sense of humour,

Cancer acts upon its defensive will

To take away T-cells’ ability to kill

I’m decoding cancer’s defensive strategies

To give patients more anti-cancer options to succeed.

The runner-up

Sophie Chambi-Trowell, School of Earth Sciences

Tiny chompers: What do the diets of the earliest mammals and reptiles tell us about modern ecosystems?

We can learn a lot about an animal’s diet simply by observing what it eats, but with a species that has long gone extinct we must instead rely on their bones. This project aims to bring together multiple cutting-edge techniques to analyse both the jaws and teeth of fossil reptiles and some of the world’s earliest mammals, which lived on the same group of islands, thereby giving us insight into some of the world’s earliest modern ecosystems.

What the judges said:

- ‘Best title. Knew immediately what the project would be about from image, and it was well supported by the text.’ — Professor Robert Bickers

- ‘This simplified well, what is actually a complex and sophisticated project. Picture is appealing and links well to the summary and project.’ — Sarah Bostock

The winner

Octavia Brayley, School of Biological Sciences

How does light pollution affect the behaviour of crabs?

Humans create light pollution from; house lights, streetlamps, and lights along beaches. This has huge negative effects on animals because they get confused from the artificial light at night which can block-out the moon, meaning they don’t know what time it is, and this can disrupt feeding patterns and make it difficult to find a mate. My research looks at how detrimental this pollution is to the behaviour of crabs and how we can minimise these effects to preserve animals.

What the judges said:

- ‘Really great picture and interesting topic, unique and thoughtful, real-world impact is clear and I liked that it’s so niche.’ — Sarah Bostock

- ‘Very creative image, which is fully relevant to the research. The caption is really clear with accessible language.’ — Dr. Jen Grove

- ‘Wonderfully engaging composition and clear explanatory text.’ — Prof. Robert Bickers