On Monday 9 May the Bristol Doctoral College hosted the ‘Research without Borders‘ festival, a showcase of postgraduate research excellence with over 100 student exhibits. Heide Busse, a second-year PhD student in the School of Social and Community Medicine, spoke to us about her experience as an exhibitor. Her research is funded by The Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Follow Heide on Twitter @HeideBusse.

On the 9th of May, I swapped office and computer for an afternoon at @tBristol science centre, where I participated in the annual “Research without Borders” event. This event is organised by the University of Bristol and provides PhD students across the university an opportunity to showcase their work to other researchers, funders, university partners and charities with the overall aim to stimulate discussion and spark ideas.

It did sound like a good and fun opportunity to tell others about my research so I thought ‘why not, see how it goes’ – immediately followed by the thought ‘alright, but what actually works to make visitors come and have a chat to me and engage with my exhibition stand’?

Luckily, help was offered by the organising team for the event from Bristol Doctoral College in terms of how to think of interactive ways to present my research – and not to just bring along the last poster that was prepared for a scientific conference. For instance, we developed the idea to ask visitors to vote on an important research question of mine. That way, visitors could engage with my research and I could at the same time see what they thought about one of my research questions!

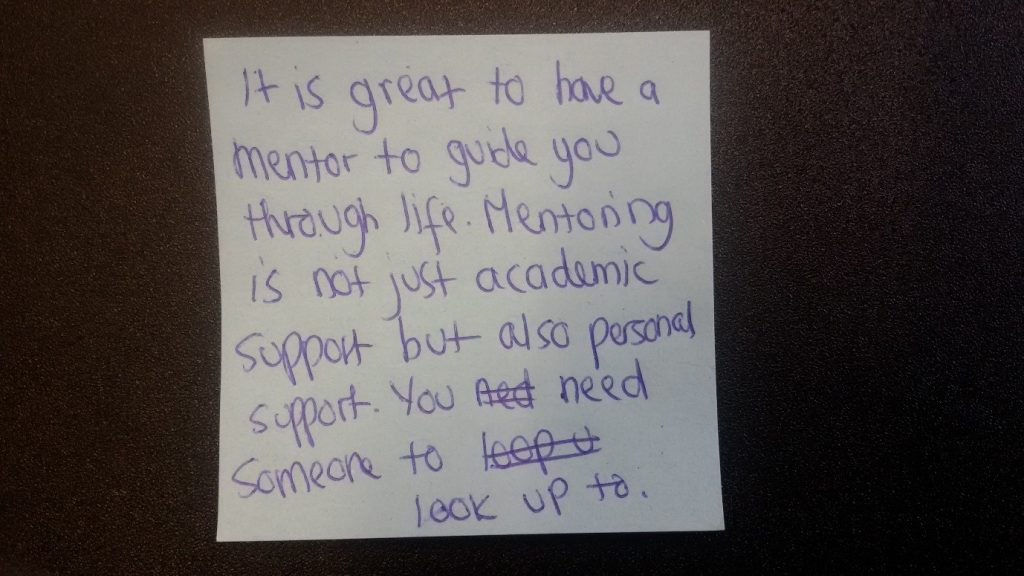

My PhD research looks more closely at the potential of mentoring as an intervention for young people in secondary schools. There are quite a few formal mentoring programmes offered to pupils but there is hardly any research in this area to suggest whether this actually works in helping to improve young people’s health, wellbeing or educational outcomes. To provide information for different audiences, I also brought a scientific poster along, as well as leaflets about my work and the work of The Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence, which funds my PhD.

On the day itself, over 100 PhD students exhibited their work in lots of different ways, including a few flashy displays and stunning posters about their research. We were given different research themes and I was included in the “population health” research theme – alongside 16 other research themes ranging from “quantum engineering”, “condensed matter physics” to “neuroscience” and “clinical treatments”.

All ready to go just in time before the official event started, I really hoped I wouldn’t be left alone for the rest of the afternoon polishing the pebbles that I had organised for my live voting. Fortunately, that didn’t happen! Time flew and without realising I chatted away for two and half hours to a constant flow of over visitors and other exhibitors – and actually hardly managed to move away to have a look around other people’s exhibitions. In total, I have been told, there were 200 people attending the event.

Visitors told me about their own mentoring experiences when they were younger, spoke about the things that mentors do and asked me questions about my research, such as why I research what I research, the methods that I am using in my research and what relevance I think my research can have for mentoring organisations- all questions that I could imagine could be re-asked in a PhD viva (in which case I guess it’s never too early to prepare!). This really made me think about my research and practice ways in which I can communicate this clearly to people who might be less familiar with the field or with research in general without babbling on for too long!

At the end of the event, I was really curious to see how many people interacted with my research and to look at the results of the live voting. I had asked individuals to vote on the following question: “Do you think mentoring young people in secondary schools has long-term benefits to their health?” and was actually quite surprised to see that 22 out of 25 individuals who voted, voted for “Yes” which indicates that there is something about the word mentoring that makes people think that it is beneficial, which itself is an interesting finding. Not a single person voted “no” and three individuals voted “not sure”.

The whole afternoon went well and made me realise the importance and benefit of talking to a variety of other people about my research – I guess you never know who you are going to meet and whether questions by visitors might actually turn into research questions one day.

How about signing up to present your research at the upcoming ESRC festival of social science, the MRC festival of medical research, other science festivals, talking about your research in pubs or talking to colleagues in the public engagement offices at your university?