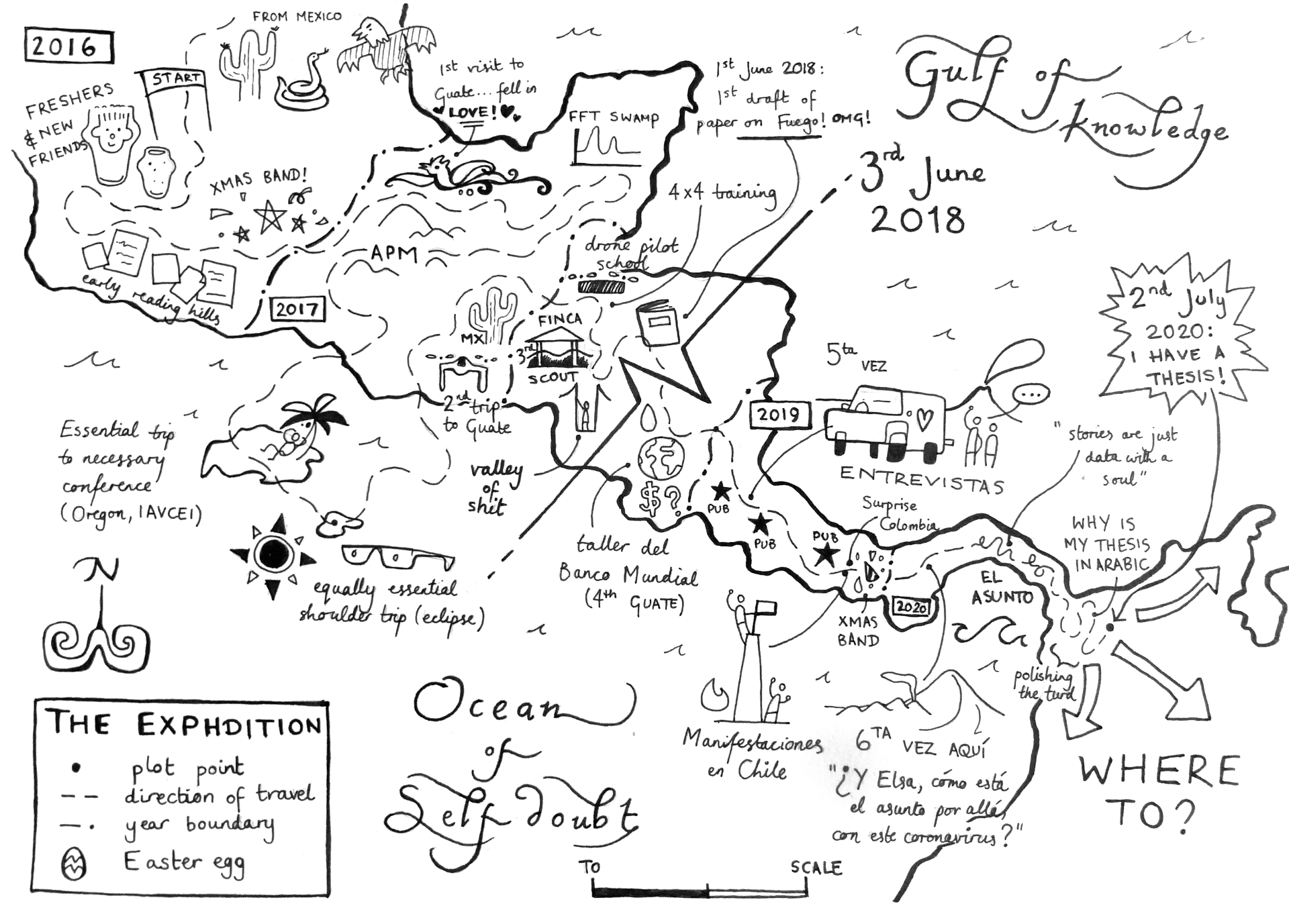

Ailsa Naismith is a volcanologist in the School of Earth Sciences who’s approaching the end of her research degree. In July 2020, Ailsa created an illustrated map of her PhD journey that received over 400 likes on Twitter. Below, she shares some of the map’s ‘points of interest’ — and explains how drawing the ‘ExPhDition’ helped her to reflect on her experiences as a postgraduate researcher.

Hello! I’m Ailsa Naismith. Since 2016, I’ve been researching volcanic risk mitigation — specifically, eruptive activity and human experience at Fuego volcano in Guatemala.

In practice, this means that I’ve been using a wide range of methods (including scientific reports, seismic data and interviews) to help forge a holistic impression of volcanic risk. The ultimate goal of my research (and recently completed thesis!) is to present the myriad perspectives of risk that coexist around a single volcano.

Illustrate to the point

I started making zines in January. I’ve always been interested in uniting art and science, so creating small pieces of illustrated text that communicate a concept feels instinctive to me.

I spent June toiling over my thesis: no zine-making that month! But then my good friend Bob suggested I illustrate my PhD journey. It was a fantastic idea, and once I agreed, the image coalesced almost instantly in my head.

Central America is both the location of my research fieldwork and an apt metaphor for the narrowing of focus during the course of a PhD. However, my course has often felt much less than focussed! I’ve met many diversions and setbacks along the way, hence the winding path I follow in the ExPhDition above.

Illustrating the journey has provided a great opportunity to reflect on these diversions, and those who helped me through.

Notes from an ExPhDition

1. FFT swamp / valley of shit

In my first year, I seized on a research idea which seemed both novel and certain to give good results. I invested a lot of time on it, gained a lot of input from other people, and realised around five months in that it wasn’t going to produce fruit. This culminated in a comment in my second-year assessment that I was a whole year behind on my research (yikes!).

The difficulty here is that you have to follow the diversion in order to retrace your steps. Even though such diversions seem like a waste of time, ultimately they helped me because they motivated me to seek help from more experienced academics. I also learned the value of having a mentor in-house who has experienced such diversions before. I was fortunate that I already had a mentor in the form of my supervisor Matt (major thanks!).

In the situation where your supervisor can’t offer this role, I suggest seeking the support of a sympathetic older student, postdoc or academic in your field. If not available in-house, perhaps look outside your department, or even beyond Bristol.

2. 3rd June 2018

Not many people can say “my volcano erupted in the middle of my PhD”. Fuego erupted on 3rd June 2018 with devastating consequences. I found it hard to process. Whatever your discipline, it’s likely that you will invest a lot of emotional capital in your PhD. Some people would say this a bad idea, but I disagree: you should own it.

For me, work is easier when you care, although caring can hurt when things don’t turn out as planned (see 1). In my case, I found that investing emotional capital was easier when I collaborated with other people that cared. Then, when I felt demotivated in my work, I could rely on discussion with those colleagues to reinvigorate my desire to contribute something towards our shared passion. And that contribution would be achieved through my PhD.

3. Chile

Geologists are suckers for an international conference, and I am no exception. I’d planned to attend a conference in Chile in November 2019 when demonstrations nationwide cancelled it. I read the cancellation email while in transit through the Bogotá customs queue.

Another piece of generic PhD advice is “Welcome the unexpected”. It’s true! If you can, when an unexpected twist places you in a new environment, search for opportunities for collaboration in your new environment. Perhaps this will show you a new career direction. For me, it kindled an interest in disaster risk reduction policy.

Drawing to a close

Reading this over, I can see this is ridiculous — how could this advice be useful for anyone except “past me”?! The PhD process is so individual.

Really, the advice I have given (follow diversions, own your emotional investment, welcome the unexpected) is quite generic. It has to be, because the specific experience that a PhD student learns cannot be generalised to others’ journeys.

But you may find that during the course of your own ExPhDition you agree with my advice, because any PhD is really an experience in gathering anecdotal evidence to support the clichés.

If you are also near the end of your journey, I encourage you to make a map of your own. It was a wonderful way of finding resolution to this huge chapter of my life.

Find out more about Ailsa’s research on the University’s Research Portal — and follow her on Twitter at @AilsaNaismith.